Our Conversation With Bob Orban, Part 3

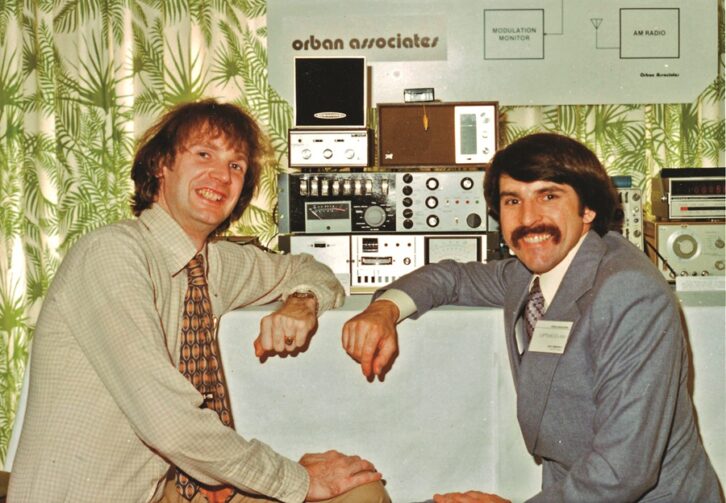

Orban’s first audio processor for FM broadcasting, the Optimod 8000, has turned 50. To mark the anniversary, Orban is sponsoring this series of interviews of Bob Orban in conversation with Radio World Editor in Chief Paul McLane. This is Part 3. (Read the earlier parts starting here.)

Paul McLane: When we spoke last, you talked about building on the success of the FM 8000 processor and getting into AM with the Optimod 9000. The early 1980s must have been a time of significant growth.

Bob Orban: The 8000 had caused us to grow rapidly and gave us the luxury of being able to take our time in terms of product development. There was plenty of money coming in, and we didn’t have shareholders other than John Delantoni and me, so we didn’t have quarterly reports to answer to.

McLane: Tell me about the design process — was it basically you sitting down and thinking? Was there a team effort?

Orban: I did the engineering design work at the time, and we had a PCB layout guy. John Delantoni, who had worked in electronic manufacturing, was responsible for production design. I didn’t do PC board layout, I didn’t do mechanical design. I did the electrical design, and what today you might call the algorithm design — although, back then, that was synonymous with the circuit design of the product.

McLane: This is all before tabletop computing, surface-mount technology and DSP took off, right?

Orban: I was a very early user of computers. I learned programming in college, first Fortran and later Algol, so I had familiarity with the concepts even in the ’60s.

My first one really was a programmable calculator, the HP 9100, around 1969. Then in 1975 we were able to afford a Tektronix 4051, one of the first devices you might call a personal computer. It used a Motorola 6800 microprocessor and a Tektronix storage tube as the display. It was programmed in BASIC. So even though desktop computing really came on the scene with the IBM PC and Apple II, I’d been doing it since 1975 with this Tektronix device.

One thing that distinguished Orban from its competitors was the formal mathematical design process we applied to our products.

For example, we started serious “design for manufacturability” by doing sensitivity analysis. That’s where you do circuit analysis and determine the effect of component tolerances on the final behavior of the circuit.

If you look back at those old Orban analog products, you’ll see components with various tolerances. That wasn’t driven by cost, as you might think. It was driven by mathematical analysis of the circuit to determine which components were the most sensitive and required the tightest tolerances.

McLane: Was that unique among processing manufacturers of the time?

Orban: I can’t speak for others. CBS Laboratories had a very good technical team and I’m sure they had access to computing facilities, but I don’t think they were thinking of processing in the same sophistication that I was at the time, particularly regarding the filter design. They were thinking of gated compressors and peak limiters embedded in other parts of a conventional transmission chain.

McLane: Now tell me about the genesis of the Optimod-FM 8100A.

Orban: Well, I knew that we could do better.

Dave Hershberger, who was working for Harris, had come up with a clever overshoot compensation scheme for a new generation of Harris stereo generators, so I needed to do something to respond to that. At the same time, my invention of distortion cancel clipping, first used in the 9000, opened up a new opportunity for FM processing.

The big weakness of the 9000’s distortion cancellation was that it required analog bucket brigade delay lines. Those were fine for AM in terms of their noise and distortion performance, but they weren’t quite good enough for FM.

So one day I had the idea that instead of using these analog delay chips, I could use the main 15 kHz low-pass filter already in the FM processor as a delay line if I applied group delay correction to it.

That was another result of computer-aided design, designing the matched filters between the 15 kHz main low-pass filter and side-chain low-pass filter for cancellation. They had to be matched in magnitude and phase over the 0 to 2 kHz region. That’s something that could not have been done without the computational resources I had at the time. I wrote programs to do that.

Now we had distortion cancellation with high basic audio quality, a very clean signal path. That allowed me to do much more aggressive clipping than the 8000 had done, to rely much more on the clipper for high-frequency control, which allowed the 8100 to be substantially brighter.

Another influence was Mike Dorrough and the Discriminate Audio Processor, the DAP 310. There were also home-brew multiband processors out there.

The problem I had with a simple multiband processor was that if you were doing purist processing for, say, a classical or a jazz format, you wouldn’t necessarily want all this automatic re-equalization that happens with the multiband compressors of the time.

I came up with the idea of variable coupling between the main part of the compressor, which was above 200 Hertz, and then a base compressor that was below 200. To avoid bringing up high frequencies unnecessarily, the basic 8100 was not a three-band like the Dorrough, it was a two-band. Then the high-frequency limiter was separate, designed to control high-frequency overload due to the FM preemphasis curve, instead of just doing automatic re-equalization.

Then I came up with the frequency contour side-chain overshoot corrector, which was my response to Dave Hershberger’s clever design. But unlike his, it did not increase clipping distortion in the frequency range below about 5 kHz.

I applied for patents on a number of these things. Patents were an important part of our business strategy, to protect our intellectual property.

An amusing anecdote: I was testing a prototype of the 8100 on KSOL in San Francisco. The late Bill Sacks was responsible for one of the other Bay Area stations. Later, when the cat came out of the bag, Bill was quite ticked off. He said, “Boy I chased that thing. I could just never quite get there. So now you’re telling me that that’s what you were doing!”

McLane: How did the market launch go?

Orban: We subscribe to the IBM philosophy, which is that when you announce a product, you need to be able to deliver it pretty much the next day, otherwise it’s going to cannibalize your existing sales.

People tested them and that that the 8100As were sufficiently better than their 8000s that upgrade was warranted. The product was a very big success for us, in fact it’s the best-selling Orban processor in the company’s history.

We eventually sold something like 10,000 units over the years, and it stayed in production for I think 10 years.

McLane: For 8000 users, this was not a modification, it was a full replacement.

Orban: It was a replacement. You also now had a built-in stereo generator. And it had the same barrier strips on the back — you could basically disconnect the wires from your 8000, put the 8100 in the rack and reconnect the wires, and you’re in business.

McLane: Were you positioning it as a processor for all formats?

Orban: It was designed so that you could go to the purest end if you wanted to, but you could also speed up the release time and reduce the coupling between the master and base bands. It was also a very competitive rock and roll, pop music, urban processor.

McLane: Are we getting into the era of presets?

Orban: This was entirely analog, so it didn’t support presets. We suggested setups in the manual, but you had to go inside the box and adjust the knobs to the manual’s recommended settings.

There were a lot of consultants who had their own secret sauce; and because the peak limiting and distortion cancel clipping systems were so strong, people started putting processing in front of it again, as had happened with the 8000. One of the biggest successes was Glen Clark’s Texar Prisms. There were also Circuit Research Labs boxes, and a number of lesser players in terms of the popularity including the Pacific Recorders Multimax.

McLane: Did it annoy you that people were putting boxes in front of yours?

Orban: As long as their checks were good in buying the 8100, that was the main thing that I was concerned with!

By this time I had learned an important lesson for anybody doing processing: Don’t confuse your own preference with the preference of the wider audience. Different people have different preferences, and that’s okay, that’s part of life.

You can either go along and help them achieve those preferences the best they can, or you can be resistant. And being resistant is just foolish.

McLane: In 1984 you introduced the 8100A/XT 6-Band Accessory Chassis. Why was that necessary?

Orban: We saw that Texar was having a big success with the Prisms. We realized that there was an opportunity not only to make a much more multiband processor but to do it in a novel way that embedded itself into the circuitry of the 8100 and that exploited its existing distortion-cancelling filters, which of course, you couldn’t do with an external product.

I came up with the idea of multiband distortion cancel clipping, where each band has its own independent distortion cancelling. It occurred to me that, because everything but the clippers are linear, you can use the single distortion-cancelling filter for all of the bands, which greatly simplifies things.

I’d had experience with six-band compressors in the 9000 and the 9100 so we knew how to do it. We came up with a hybrid that plugged into the 8100A with an umbilical cord into a connector in the back, and you moved a few jumpers on the 8100’s printed circuit boards.

The 8100A/1 made those provisions, and you could upgrade them. [See a 1986 manual for the 8100A/1 from the website World Radio History.]

8100A units could be field upgraded to 8100A/1 status via the Orban RET-27 upgrade kit. It required soldering to the backplane and replacement of several PC cards. According to the XT2 manual, the upgrade could be expected to take about an hour, and the XT2 manual contains installation instructions for the kit.

When we got the 8100A/XT out on the market, some people pushed back against the tuning, so I did more work on that. I also discovered that it seemed to work better when the top-band compressor was controlled by the side chain of the band below the top band.

Those two modifications, along with additional tuning controls, became the 8100A/XT2, and it seemed to be exactly what the market was looking for. Again it stayed in production for a number of years.

McLane: What does the success of these products tell us about the radio marketplace of the time?

Orban: They wanted it louder, they wanted it brighter, they wanted it cleaner.

Those three requirements require tradeoffs. Usually when you push one, you get less of the other. Our goal was to offer a toolkit that allowed you to push that as hard as you possibly could, with the best compromise depending on your preference.

It was not up to me to dictate user or program director preferences. They knew more about programming than I did, and they did focus groups, they watched the ratings. I just provided them with the tools to realize what they wanted to do.

We wanted to serve any format, from the BBC doing classical music all the way to an aggressive rocker in the New York City market.

McLane: Meanwhile you were introducing products on the TV side.

Orban: The Optimod-TV 8180A, introduced in 1981, was basically an 8100 without a stereo generator.

Around the same time, CBS Technology Center, the successor to CBS Labs, had come out with their second-generation CBS loudness meter and an associated loudness controller.

There had been an FCC docket on loud commercials. I saw an opportunity to address the FCC’s concerns and introduce a good-sounding processor that could be tuned appropriately for television. It was based on the 8100, which is a highly tunable processor.

We licensed the loudness controller and loudness meter technology from CBS Technology Center — we never brought out a commercial version of the meter, it was just too expensive with analog components.

I did some mathematical transformation of the original filters in the CBS IP package to reduce the cost, but even so, it would have been very expensive. When we finally introduced the free Orban loudness meter in DSP in 2008, one of the goals was to finally make the CBS loudness meter available to the wider public after a gap of many, many years.

So in 1983 we introduced the 8182 version, which added Hilbert-Transform clippers and a CBS Loudness Controller to the original 8180A.

Hilbert-Transform was based on the work of the mathematician David Hilbert, which in turn was based on work by Michael Gerzon, who was active in the Audio Engineering Society and a published author. He figured out how to do an RF clipper without using RF modulation by doing a model.

I borrowed his work and combined it with distortion-cancelling ideas of mine. That turned into the Hilbert-Transform clipper, first used in the 8182 Optimod TV but later also in the Optimod-HF 9105 for international shortwave.

McLane: How did the TV side of the industry respond to your products, how were sales?

Orban: Slow but steady. TV stations did not think of their revenue in terms of loudness wars, for very good reasons, but they were under pressure from the FCC for the loud commercial issue.

We offered them a package tied up with a bow that would solve their loud commercial problem and provide a comfortably listenable audio stream. People could just relax and enjoy and not even think about it. Dialogue was intelligible. Commercials weren’t too loud, everything was consistent.

The 1990s was a golden age of intelligible dialogue, before a lot of the practices that have caused such a big problem.

McLane: A couple of years later you added the 222A Stereo Spatial Enhancer.

Orban: Eric Small had introduced the StereoMaxx, a stereo widening tool that was getting popular with broadcasters as an add-on. Again we saw a business opportunity to put our own spin on it. It worked completely differently from Eric’s device and had several advantages. It didn’t amplify reverberation excessively.

We also had the 275A Automatic Stereo Synthesizer, which had automatic detection and recognition of stereo and mono programs, and automatic stereo synthesis. That was a result of the transition to BTSC stereo. There was a lot of legacy mono material out there still being broadcast.

McLane: Speaking of which, how has the quality of source material affected these conversations? Have you seen that change dramatically?

Orban: One dramatic thing that happened in television was that the networks finally got off the AT&T Long Lines and were able to transmit 15 kHz audio for the first time, instead of 5 kilohertz. Television sound suddenly became high-fidelity. Between that and BTSC stereo, probably the biggest change in the consumer space was in television audio.

Vinyl records could sound very good and they were played on the air. Tape carts had their problems; they were convenient, but there were the endless phase issues.

Whatever you might say about early CD sound from an audiophile perspective, CDs were a godsend from a broadcast perspective, because by and large they didn’t skip and they cued easily. They didn’t require cleaning gunk off a stylus, or head alignments.

So radio had had access to high-quality, high-fidelity source material since the late 1940s when the LP record was introduced, and then, starting in 1957 with the stereo LP. As far as the audience was concerned, CDs were a marginal improvement in audio quality but a big improvement operationally.

Then things went backwards. Stations started using MP3s as broadcast sources, which I thought was a big mistake. The people who had thousands of MP3s on their playout systems eventually became second-class citizens when hard disk got cheap enough that you could do linear audio on the playout systems. But that was later.

McLane: What else do you remember from that period?

Orban: It was a great time for us. It was exciting. We managed our growth pretty well; we didn’t take on debt.

When we finally were in a position to sell to AKG, we were in a very good position. But that’s the story for next time.

The post Our Conversation With Bob Orban, Part 3 appeared first on Radio World.