Metadata as a Second Language

The author is a development engineer for Wheatstone. This is excerpted from the Radio World ebook “Streaming Best Practices.”

If content is king and metadata is queen, it would be perfectly reasonable to expect that we have all the metadata standards worked out.

But, in fact, we’re far from anything of the sort. Metadata tags, types and formats for song title, artist, etc., are all over the place, and getting that data from your automation system out to the CDN and onto listener devices is a lot like trying to learn several languages at once.

Metadata, as we all know, comes in the form of song title and artist name as well as sweepers, liners, station IDs, sponsorships and text of all sorts that show up on your listeners’ players.

But that’s just the tip of the metadata iceberg.

If you have a live program that you want to turn into a podcast for later download, we use metadata as an easy way to trigger when to start and stop recording. Metadata is used to trigger ad replacements from on-air to in-stream and to switch between sources when, say, during a live sporting event certain programming needs to be replaced by streamable content. Specific metadata syntax can trigger a switchover to another source and to target ads by location or demographic, all dynamically and with incredible precision by Zip code, geolocation, device type and more.

All of that starts and ends with metadata, which has its own standards, protocols and ways of doing things at each point in the process.

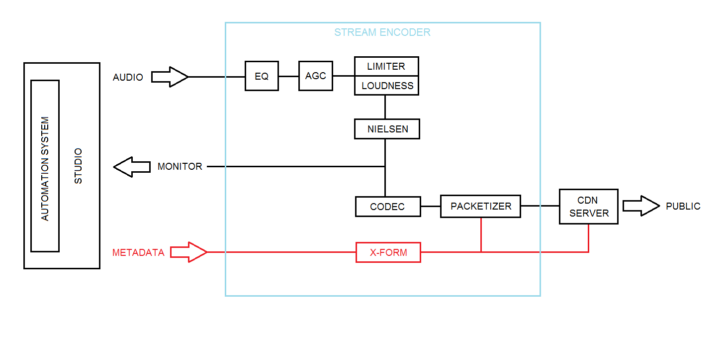

On the one end is the CDN, which takes streams and metadata from the station studio and sends it out to listeners. On the other end is your studio, which includes your automation system, your routing system and an encoder such as our Wheatstream or Streamblade appliance that performs all stream provisioning, audio processing and metadata transformation and sends it all off to the CDN.

The stream encoder has three jobs: 1) process and condition the audio, optimizing it for the compression algorithms to give it that particular sound the same way an FM processor does; 2) encode, packetize and transmit the program over the public internet to the destination server, the CDN; and 3) handle the reformatting and forwarding of metadata from the automation system to the CDN.

To handle the important task of handing over the right metadata at the right time and in the right format, our Wheatstream and Streamblade encoders use transform filters written in Lua (see Fig. 1), an embedded scripting language that can parse, manipulate and reformat data based on specific field values, content, or patterns that would be difficult to define with conventional methods.

Lua transform filters give us a way to map what’s coming in to what’s needed to come out of the studio in order for CDNs to be able to pass on the metadata.

It starts here

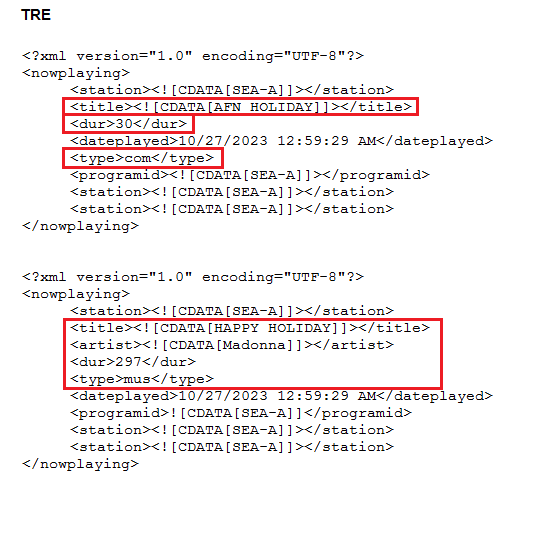

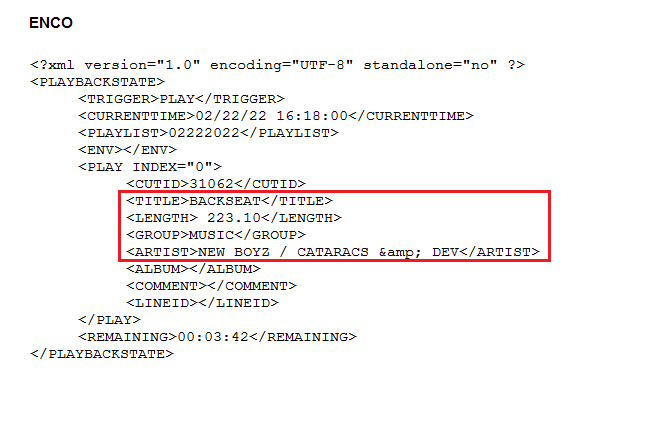

For broadcast purposes, metadata begins in the studio. Artist and song title metadata typically comes from the automation system and is often synced with the music. Metadata is received by the stream encoder on a TCP or UDP socket, and most commonly arrives formatted as XML. What happens after that depends to a large extent on the transport protocol being used by the CDN, the details of which differ because there are no universally accepted standards for handling metadata (see Figs. 2 and 3).

What the CDN sees

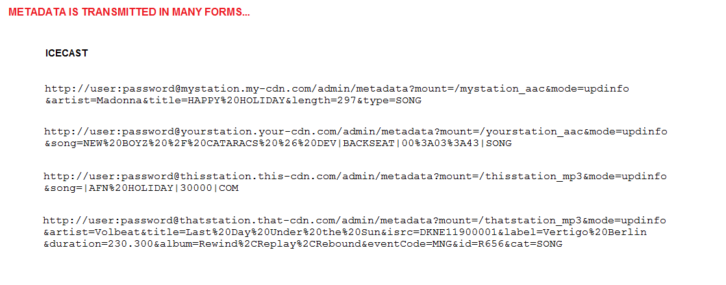

CDNs use various protocols, and depending on the protocol, metadata is either injected into the audio streaming, in the case of protocols HLS, Triton MRV2 and RTMP, or sent separately, in the case of the Icecast protocol.

For Icecast, metadata is sent as an independent stream separate from the audio (Fig. 4). HLS, the HTTP Live Streaming adaptive bitrate streaming protocol by Apple, is a common protocol used in contribution networks that feed into CDNs, and many CDNs have also adopted HLS for carrying metadata with audio in the same stream.

For example, in HLS, metadata such as artist, title, duration, album, album art, fan club URL, etc., are formatted as ID3v2 tags and inserted into the MPEG3-TS segments between AAC frames. Metadata involved in switching between program content and ad-insertion is commonly written to the manifest file (constantly updated with the addition of each new TS segment and aging-out the oldest) in the form of SCTE-35 splice points.

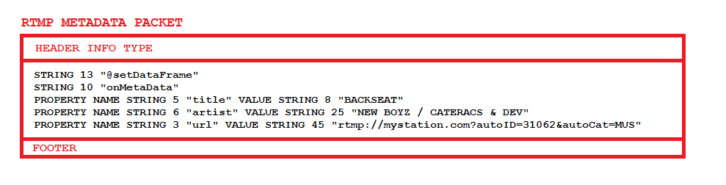

Meanwhile, RTMP metadata is encoded into a “setDataFrame” message using the Action Message Format (AMF) developed originally for Flash applications (Fig. 5). (Despite the demise of Flash video, RTMP itself is still in active use for backhaul streams up to the CDN.)

Metadata is represented in serialized structures called AMF arrays. The entire message is wrapped in a standard RTMP packet and inserted into the outbound stream along with the audio packets.

A CDN knows when to switch to ad insertion and when to switch back to normal programming based on the category of the metadata itself. Most CDNs are expecting incoming metadata events to be categorized into three types: songs, ads (spots) and everything else (sweepers, liners, station ID, PSAs, etc.). Ad insertion begins the moment the CDN receives a COM or spot event and ends when the CDN receives any other event. Metadata tightly synced with audio is critical for making sure that data matches the actual audio for spots as well as music.

There are many ways to customize and create special conditions that can be transmitted to the CDN with the proper signals, as long as both parties agree on what the signals are.

Job 1

Job No. 1 for our Streamblade and Wheatstream encoders is to hand off as much relatable and useful data as possible to the CDN, whose main function is to serve your stream to thousands or tens of thousands of listeners.

The twin facts that A) your program and all associated metadata passes through the CDN’s servers; and B) they know who is listening, from what location, and for how long mean your CDN provider has the ability to give you a whole suite of add-on services.

A big one is ad insertion or replacement, which is usually geographically based, but could also be tailored to whatever can be deduced about the individual listener’s tastes and habits.

Geo-blocking, logging, skimming, catch-up recording and playback, access to additional metadata (e.g. album art, fan club URLs), listener statistics and click-throughs, customized players, royalty tracking, redundant stream failover, transcoding from one format to another — these are some of the services that CDNs typically provide. Thus, the CDN basically controls the distribution of the stream to the listening public. It is the responsibility of stream encoders like our Wheatstream Duo and Streamblade — the origin server to the CDN’s ingest and distribution servers — to make sure that the CDN gets the right data at the right time and in the right format.

Especially with regard to metadata, the stream encoder is the mediator/translator between the automation system and the CDN that can open opportunities for ad revenue and more.

Streaming is an actively evolving technology, and it’s probably still in its infancy. The queen of streaming, metadata — how it is carried, how it is used — will likely continue to evolve along with it.

[Do you receive the Radio World SmartBrief newsletter each weekday morning? We invite you to sign up here.]

The post Metadata as a Second Language appeared first on Radio World.